For a linguist, researching cross-neurotype spoken communication between autistic and non-autistic people, I spent an awful lot of my doctoral period thinking about non-human communication.

There’s a comment to be made there, I’m sure, about the rife dehumanisation and stigma that many autistic people experience, but my motivations weren’t quite so poetic at the time. More, I had an ecological participatory sense-making itch I needed to scratch...

I was perturbed by the problem of why communication between people of differing neurotypes often falls short – borne out most evidently in the sometimes stark ruptures in mutual understanding we see between autistic and non-autistic speakers – yet, given the right circumstances, cross-species communication can flourish. It’s an unfinished thought, one I only really hint at the resultant book via its references to honeybee-plant mutualism, but one that, I was reminded very recently, has been tugging at my sleeve for almost twenty years.

A few weekends ago my sister and I were summoned to sort through our parents’ attic in preparation for their long-anticipated downsizing. Down through the dusty hatch came nursery-wall pasta-paintings, half-completed Care Bear sticker books, questionable tie-dye crop tops and shoebox upon Clarkes shoebox of ephemera: tickets, stamps, photos from school camp, certificates for ‘good behaviour’, love letters written in ink and quill by my teenage goth boyfriend on paper he’d hand pressed and bound in ribbon and, mixed between them, emails I’d received at the dawn of a new century before the ‘Cloud’ was a thing, and printed out on a mix of printer and coloured paper for safe-keeping.

Steeping myself, as I did, for hours surrounded by the artefacts and small intimacies of a life (the sucked ear of a shabby soft toy and cracked clarinet reeds, the favourite pebbles and clumps of fool’s gold, the scratchy shaky handwriting of my grandmother always, without fail, beginning her missives ‘Dear Funny Face’) conveyed a dizzying sense of me-ness. Disorienting, too, to see how many of the forgotten loves of my childhood had in fact been whispered into chipped polystyrene cups, down along pulled-taught string, to resonate out into adult life counterparts; how a deep fascination with the pollination cycle of the black-sap-dribbling cherry tree in our front garden, evidenced in detail in a 7 year old’s illustrated love-poem to the tree and the bee, could show up almost verbatim, in a book written decades later...

Among the printed emails was just part of an exchange I’d shared with a truffle hunter, back in 2003.

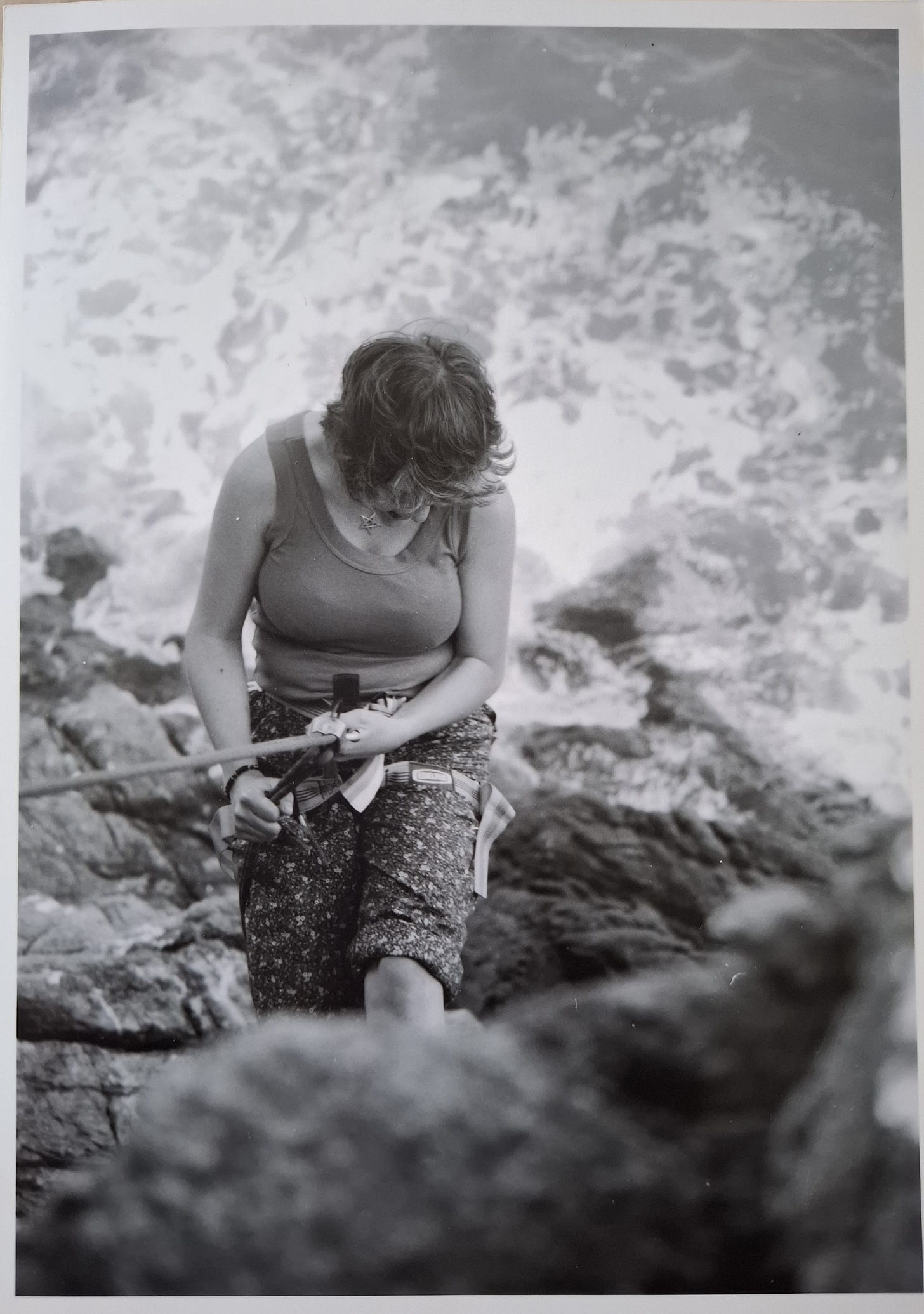

I remember the context of the exchange really clearly. Not long prior to this I’d quit my first attempt at university to go and live in a commune in the wilds of Aberdeenshire. For an overwhelmed, overstimulated, undiagnosed autistic drop-out, I couldn’t have found a better medicine. Drumblair Lodge was set back off a B-road in the valley of Forgue just down from a single malt whisky distillery and pressed into the foot of a large, thicketed hill. Days were spent working on the veg beds and slowly transforming the old, dilapidated chicken shed into a recording studio for main the main protagonists in this collective, a band named Delicate Awol. Evenings were spent around the large wooden table before the Aga or working our way through the folk, jazz and prog vinyl collection in the listening room of this sprawling old manor house. Weekends were for life drawing, walks, more music, and occasional rock-climbing ventures guided by our housemate Patrick, an artist friend of the band with orienteering expertise.

Putting my hands in the mud every day and learning to grip rock, waking to the cacophony of rook-caw morning song, sipping Caro’s homemade spirits and snacking on scavenged hedgerow berries, warming my skin before real, roaring flames; my highly-strung neurodivergent body unwound slowly into a soft sensuality that made it easier and easier to see myself as one animal organism living among so many other animals and non-animal others. The spiders spinning the webs at the top of the porch that caught the morning dew, the shrews that scuttled across the long and bumpy driveway at dusk, the tall trees rustling in the wind, the spindly-bodied tomato plants, the mushroom rings that sprung up like spongey stone henges over night in the field where the sheep were free to wander… We were all coinhabiting this idyll together. The more I re-membered my body – the more I brought it back into a vivid engagement with itself and the world after what was, realistically, probably quite a dissociated few years before – the closer I felt to all bodies.

So it was while I was living at Drumblair, marvelling at mushrooms and starstruck by the novelty of clear night skies, that I had my first taste of truffle – a dark firm slither atop a handful of ravioli as the starter at the wedding breakfast of the drummer in the band. Its muddy, umami mouthfeel set something sizzling in my brain and the next few weeks and months essentially became my truffle era: what through a neurodivergent lens might elsewise be described as the period of my intense special interest in truffles.

For days after the wedding feast I felt giddy with truffle-lust. Truffles, you may or may not know, are the underground fruiting bodies fungi, who (yes, I’ve chosen ‘who’ not ‘which’) live in close symbiosis with trees – in Europe, usually oaks, hazels or beeches. They aren’t easy to farm or to grow intentionally, and forming out of sight, as they do, truffles aren’t always easy to find in the wild. They require the expertise of a ‘trifolau’ (or, ‘truffle-hunter’) and a truffle-trained dog… or pig. Truffles, you see, post up to the surface an olfactory calling-card that mimics the pheromones of male pigs, drawing desirous snouts down through the dirt up to three feet in search of the pungent prize. Banned in 1985 in Italy due of the damage they caused in their foraging frenzy, dogs were trained to take over the role.

Truffles were in me, both literally and figuratively, now, and I needed to know more.

Somehow – I’m really not sure how – my dial-up search for truffle hunters on an early internet led me to a man named Charles Lefevre, whose email address I copied and pasted into the space above a message (found twenty years later printed out and tucked into a box in my parents’ attic) with the following (in retrospect, slightly unhinged) opening:

“Hello Charles,

I recently had truffle ravioli at a wedding reception and before then had not really given them much thought. But since this encounter they keep entering my thoughts – what strange little beings!...”

My email went on to ask if he might tell me a little truffle lore. What I didn’t realise at the time – but have, in writing this post now learned – was that in addition to being a truffle enthusiast, Charles Lefevre was a then very recent PhD graduate in Forest Mycology, and has since become a world truffle expert. Charles’ response was everything I could have possibly hoped for:

“I do work with truffles… they’re around me all the time… Haunting little beasts. They don’t just grow on you, they grow into you. Have you had any flashbacks… vivid experiences of truffles when you haven’t had any around you? Every truffle hunter I have ever met says the same thing about them… they are magical.

Truffles depend on animals to eat them, but we can’t see them like some red fruit. Instead, they produce the olfactory equivalent of red, and powerfully enough to work its way up through the soil and capture our attention as we pass through the forest. The aroma of truffles contains compounds that work directly on our brains to influence our behaviour. The most commonly discussed is a chemical called androstanol that acts as a pheromone in many other mammals. Truffles also clearly produce an olfactory cocktail that has the ability to imprint itself in our memory where it can continuously remind us of the experience of eating a truffle. The more effective a truffle is in getting us to eat it, the better it will manage to reproduce [….] The difference between mushrooms and truffles is that all truffles depend on animals to disperse their spores. They need for us to eat them. Thus, it’s questionable whether they serve our purposes or we serve theirs…”

Charles’ (very kind and generous) response confirmed the whacky suspicion I’d had that my mind was now full with truffle-song: as if scent were sound and I’d been ear-wormed. In the same way that plants lure pollinators with ultraviolet Xs marking the nectar-filled sweet spots, those stinky, lumpy, dark balls were calling to me up through the forest floor.

Over the following few days, I set out to exorcise this imp: or at least to put into words the feelings that the truffles had evoked. I found myself writing about a lonely truffle hunter, doggedly pursuing a lifelong vocation through a declining landscape with dwindling fecundity. I wrote about Porcienta, his trusted sow, ever lusty and never sated, always chasing what was just out of reach. And I wrote about a single black truffle, so desperately wanted but never found, dormant and unconscious underground until the pressure of its edges against soil at the peak of its ripeness awakened an exquisite sensitivity indistinguishable from consciousness.

I could not, back then, imagine anything more sad or more beautiful. I suppose, on reflection, I was probably writing about myself as much as the truffle. About the coming-into-beingness in proximity with the land, or about the delectable discomfort of feeling oneself in and through relation to others, to the great web of it all. Still an unfinished thought, really.

The story I sadly no longer have but the emails I do: what treasure! And over twenty years on here I am, still thinking about truffles.

Haunting little beasts indeed.

After an encounter with “chicken of the woods” a few years ago, which I wrote about at the time (but think it might be too unhinged to share publicly!) I have long suspected that some fungus fruiting bodies are asking to be eaten.

I think we mignt be a similar age, I found your description of childhood mementoes very nostalgic and I’d forgotten all about printing off emails. glad you got such a lush reply from the truffle hunter. Love how you told this story. Glad to have found someone else writing about interspecies connections on here 🐗🐕🐾🌳🍄🟫

This was a beautiful piece!